Published Attitude: The Dancer’s Magazine Summer 2010

Published Attitude: The Dancer’s Magazine Summer 2010

In the late Eric Rohmer’s Love in the Afternoon, the film’s hero, Frederic, rhapsodizes about the city: “I love the city. The suburbs and the provinces depress me. Despite the crush and the noise, I never tire of plunging into the crowd; I love the crowd as I love the sea, not to be engulfed or lost in it, but to sail on it like a solitary pirate, content to be carried by the current, yet strike out on my own the moment it breaks or dissipates.”

Those feelings are familiar to anyone who’s spent time coursing through a bustling, vital, metropolis; what a pleasure to discover that Rohmer’s spirit lives on in the work of Larry Keigwin. Keigwin+Company’s spring show at New York’s Joyce Theater showcases this peerless chronicler of the public and private modes of the way we live now. It isn’t just energy he captures, though if energy were enough of a barometer for the maddening, bracing world of city life, Keigwin’s world is the ne plus ultra of this inimitable kinesthesia. Look closer, though, and you’ll see the eccentricities of entitlement, melancholia, self-possession and sexuality that define the urban, urbane esthete of a teeming, skyscraper world: no limits, no brakes.

Caffeinated, originally commissioned by NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, demands explosions of energy to fuel its not-quite-human Pac-man universe. Cups in hand, athletically dressed in black and white as if late for a spinning class, Keigwin’s dancers depict life as a race comically fueled by the opiate of the masses. Coffee enables super-human feats, from arms that semaphore wildly to hyper-attenuated leaps, spins, jumps and abrupt changes of direction that enable them to dodge traffic, designer poodles, spatially challenged tourists, or careen back to that storefront window where a fabulous coat is being displayed. Acting counts here: the frenzied single-minded dementia and the caught-unawares exhaustion when the caffeine high dissipated, told as much of the story as the movement. The audience, amused and rapt, saw themselves, proudly.

A dance composed of six parts, Mattress Suite is an exploration of polymorphic relationships coming to terms, especially with sex. It began with a bride and groom about to take that vow: hysteria erupted like little earthquakes as the woman (Nicole Wolcott) found herself caught between the girl she was and the grownup she must now become. The groom (danced beautifully by Keigwin) expressed his own anxieties in a volley of slicing leg extensions and a touching pantomine with a ring that symbolized a noose around the finger of one not quite ready to make the leap. The genuine anguish in his second solo (set to Bill Wither’s “Ain’t No Sunshine”) recalls the works of painter Francis Bacon, especially the portraits of his lover George Dyer, whom Keigwin faintly resembles. Keigwin made the mattress—sometimes hoisted aloft, used as either a wall or trampoline—the seat of nagging questions about the joys and limits of intimacy. The married couple’s loving, combative pas de deux preceded a surprising, sensual ménage a trois for Keigwin, Aaron Carr and Matthew Baker; the three dancers rippled in sync like the pages in a flipbook. This sequence’s movement was subtly graced by humor: whenever Keigwin showed one of his paramours too much attention, cautionary glances passed from one to the other, as if to remind each of the relationship’s rules and boundaries.

Bird Watching felt like a mashup of Swan Lake and My Fair Lady’s “Ascot Gavotte.” The lights rose on a quintet of dancers clad in black tutus whose fixed stares were superior and vaguely threatening, like birds we’d loathe to meet in a dark alley, or a gala at the Met. Keigwin’s dance owed as much to National Geographic as it did to the ballet; the mimicry of swans (or pigeons, take your pick) commingling, at rest or in flight, was unerring. But so are the semblances to that which is unmistakably human in those blank stares brimming with guile. Bird Watching suggested how minimal the difference between a creature in the wild and that which exists in our sleek urban jungles as Matthew Baker, Ashley Browne, Aaron Carr, Kristina Hanna and Liz Riga strutted and preened with a don’t-mess-with-me finesse no mere woodland creature could match.

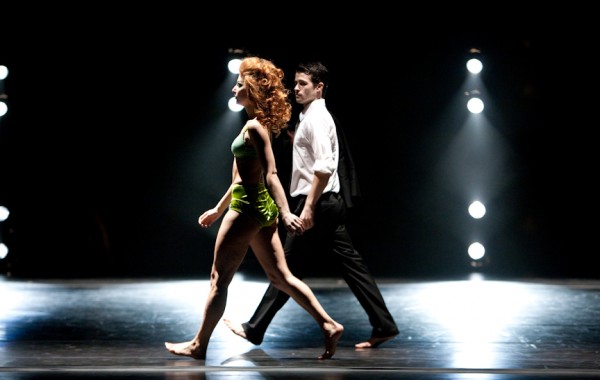

2008’s Runaway closed the evening; like Bird Watching, its title embodies a double meaning. This piece took over the entire theater in a blizzard of sound and lights, a fashion show at the end of the world. Again, the walk dominated as company members (here, joined by guest performers) propelled themselves up and down the aisles and across the stage. It’s Helmut Lang by way of Galliano: in contrast to their black-suited partners, the woman sported Fritz Matson’s bright Day-Glo minis and Marie Antoinette coifs that had a life of their own. The hair withstood a witty pileup of bodies, and sudden, avaricious leaps into the arms of various men, followed by eerie freezes, as if the dancers had turned to stone. Runaway’s world felt both futuristic, and ripped out of Thursday morning’s New York Times Styles section. But the current that runs through those automatons also evoked an endemic, dichotic aspect of the focused, motivated city dweller that asked us to consider the depths masked by our energies: individual mysteries waiting to spill forth or the soulless futility of lives lived on the run?

Keigwin+Company at the Joyce Theater, New York, March 2010

Artistic Director Larry Keigwin

Lighting Design Burke Wilmore (“Runaway” Scenic & Lighting Design originally by Clifton Taylor)

Costumers Jen Houghton, Elizabeth Payne, Fritz Masten

With: Matthew Baker, Ashley Browne, Aaron Carr, Kristina Hanna, Liz Riga, Ryoji Sasamoto, Gary Schaufeld, Nicole Wolcott

And: Kameron Bink, Charlotte Bydwell, Carlyle Eckert, Kevin Ferguson, Kile Hotchkiss, Anila Mazhary, Corey Pancake, Rachelle Rafailedes, Jaclyn Walsh