“I wanted to sound an alarm. But nothing had happened.”

Alfieri, A View from the Bridge by Arthur Miller.

In the current revival of A View from the Bridge, the alarms ring throughout. The play’s big Greek epiphany centers on a matter of trust: Eddie Carbone, the dockworker, commits a betrayal so huge that there’s no recovery, no forgiveness to be had, which means he will meet an end worthy of Euripides. At its mid-1950s premiere, this rat would certainly resonate with audiences still reeling from the activities of Joseph McCarthy, Roy Cohn and the House Un-American Activities Commission. But I suspect they were just as horrified (or titillated) by the accusation that comes earlier in the piece, one leveled at the sensitive, blonde Italian Rodolpho: Eddie accuses him of homosexuality in a desperate attempt to dash the immigrant’s blooming romance with his niece Catherine (for whom he harbors incestuous feelings). When Eddie kisses Rodolpho it feels like a rape worse than the one Eddie inflicts when he alerts the immigration authorities later in the play.

The play’s sub-theme was always there: what makes a man? Is he the blustery, stolid Eddie, the one who gets waited on hand and foot by the women in his life? Or is it Rodolpho, a man in love with culture, one who can cook, sew, even carry a tune? The better-man question is one that’s haunted me my entire life, though I doubt it’s one Miller was much interested in. Still, my contemporary thoughts find it ironic that present-day implications of gayness feel sadly indivisible from those of the Eisenhower decade. The disparagements continue (I love the recent report from Africa where zeolots showed pornographic films that featured scat play, as if gay men invented such fetishes). The big difference between past and present? The oppression is no longer underground. The newspapers trumpet assaults both physical (bashings, murders) and psychic (In the Army?—stay in the closet. Wanna marry your partner?—tough luck, you tax-paying idiot).

Similiar feelings arose the week before during a performance of The Pride, a new play by Alexi Kaye Campbell that, one hopes, will have a life outside New York once it ends its too-brief run at the Lucille Lortel Theater. Its diptych structure exploits the friction between gay relationships straddling two eras: 1958 and 2008. Of the two, 1958 felt more compelling as drama, sociology and a portent of issues that invade the gay present-day—loneliness, societal persecution, conversion therapy. If you grew up in an oppressed era (as I did) these issues tap into sensibilities that lie just under the skin, ones hard to dismiss.

Such wariness feels justified today. The cries of lying, ill-informed right-wing zealots—lovely male role models, no?—grow louder in the town square. The church (especially the Catholic Church) refuses to clean its own house, but continues to cast aspersions that would be laughable if their influence wasn’t so pervasive. The friend many thought we had in the White House is dragging his heels. The times aren’t changing as fast as they ought, and the strain is beginning to show. Sound the alarm.

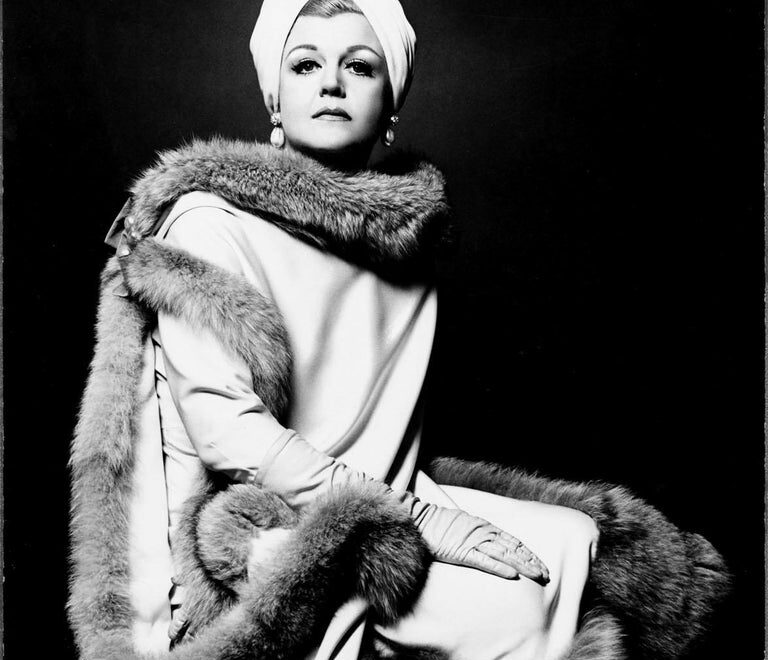

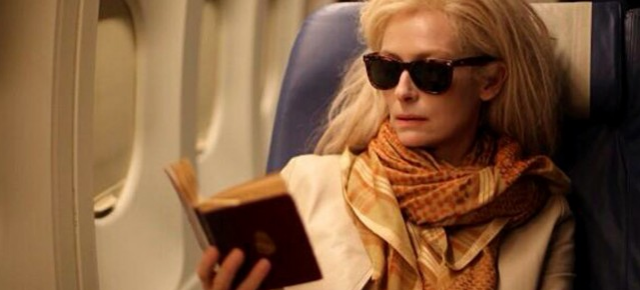

Top, Jessica Hecht, Scarlett Johansson, Morgan Spector and Liev Schreiber in A View from the Bridge. Bottom, Hugh Dancy, Ben Whishaw in The Pride. Photo, Sara Krulwich.