The mournful qualities of fall—all those dying leaves whose color mimics that of dried blood—complement the inaugural season at New York LiveArts, the still-young merger between Dance Theater Workshop and Bill T. Jones/Arnie Dance Company. With evergreen works by Jones and John Kelly being remounted, how intriguing that so far the theater unfolding in the audience proves more heart-stopping than the work onstage. Look around during the show: the tear-strewn faces, those sobs, speak both to a deep connection with work that sprang from a time when the arts world literally broke in two. Some of the folks who’ve made the pilgrimage to see Body Against Body (closed Sept 25), a revival of Jones’ seminal pieces from the 80s, and now John Kelly’s Find My Way Home (running through Oct 29), were there when these works premiered. At a time when death and political caprice shadowed what, for many of us, should have been halcyon days, revisiting the art that arose from it brings back all the anger, the sadness, the uncertainty and confusion. So potent is the phenomenon of grief during these shows that an idea occurred: some intrepid artist could distill it into a performance piece of its own, an investigation of grieving witnesses wrestling with history, juxtaposed against the reactions of those too young to have experienced the dark Helmsian days of hate politics and the decimation wrought by AIDS.

Bringing back the dead is a brilliant marketing stroke, and LiveArts is to be commended for essentially taking on the role of revivalists/archivists. Though never less than fascinating, the payoff is mixed. With Body the dynamism of the company, combined with the sheer strangeness of the work, managed to shuck off criticisms of “the museum effect.” The energy and commitment overcame a multitude of obstacles, like the schematic repetition in choreographic design. Sure, some will see the ghosts of Arnie Zane and the young Bill embodied especially in the tall-short pairing of Talli Jackson and the protean Erick Montes in Monkey Run Road (Montes was equally thrilling in the remarkable Continuous Replay). Nostalgia aside, though, these were rapt, engaging re-mountings whose acquaintance it was an honor to remake.

Whether that’s the case with John Kelly’s Find Your Way Home I’m not so sure. Be it on Broadway or in an East Village basement, Kelly remains one of the most riveting artists New York has ever produced. Often he invokes the presence of a sinister Charlie Chaplin; in Home I saw echoes of the theater of Kelly contemporary Charles Ludlam, the 80s artist whose toolbox also deployed the tropes of earlier eras.

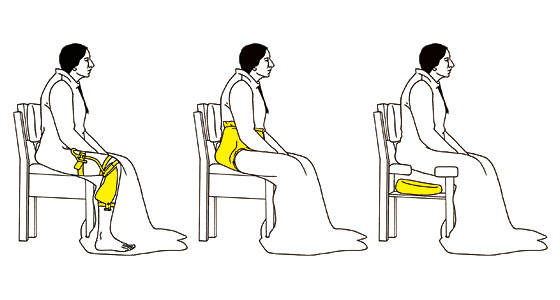

But then summoning ghosts is Kelly’s stock in trade (his other unearthlings include the artist Egon Schiele and Joni Mitchell circa the Summer of Love). Find Your Way Home is an updated version of the Orpheus/Eurydice myth that deftly balances silent film, Greek myth and the flapper-elegant Roaring 20s with economy and a light touch I found more worthy of admiration than involvement. All the evening’s style and restraint failed to forestall a restlessness I sensed wafting from the audience; you couldn’t help but study the grace notes, such as a repeated lift (the 1st by two men, the 2nd by a het couple) that owed much to the Kama Sutra and the cast’s deft, subtle acting. The grand flourishes (those lovely original set and costume design by, respectively, the late Huck Snyder and Gary Lisz, the dramatic spot-lit of lighting designer Stan Pressner) exposed what felt like a hollow underneath; despite the intelligent elegance, Home failed to deliver a liftoff to exaltation.

But something happened that rendered questions of artistic relevance moot. Kelly places a coughing fit in the beginning and the end of the show that summoned my own emotional retrospect: at a dinner party in the late 80s I and the other guests sat stunned as a young man, not-so-obviously sick, all but hacked his lungs out. The evening’s high-spirits fled; later I found out he died, already preceded, soon to be followed, by a trail of other handsome, talented men whose friends and families would see them through to the end of their too-short lives. That cough has haunted me in the days since. Such gestures—our Grant’s Tomb, our Lincoln Memorial—speak to these work’s true value, and why they must endure. The answer lay in the audience response, where cries of enduring grief resounded like a gift bestowed.