So, so you think you can tell Heaven from Hell, blue skies from pain.

Can you tell a green field from a cold steel rail? A smile from a veil?

Do you think you can tell?

Roger Waters, Wish You Were Here

By the time we made it to Washington Square Park, 1993 was already half a day old. In the sun’s glare, a mirage of brick brownstones bordered the eastern end like red smoke; a few feet away, manic pigeons pecked for food under tree branches sprayed like dull straw against the blue sky. Lingering traces of the previous night’s New Year’s Eve were rare—maybe the wind swept up the celebratory remnants and whisked them away, leaving only the litter of cigarette butts and a few leaves.

Wind-blushed faces hurried by in a blur, revved to heightened velocity by the static cold. From a bench at the park’s southeast corner Dan and I watched boyfriends with girlfriends, couples pushing strollers filled with pastel bundles, dyed rainbow and black-haired grunge artists. Like ants they crisscrossed and dodged each other on the now-circular, now-straight grid of walkways, shortcuts to somewhere else—a festive New Year’s Day open house, a movie at the Angelica or some family gathering.

The day’s surreal beauty unlocked a memory. Dan used to go on about retiring to a communal house once he’d reached his doddering years. The place would have a porch (mandatory), and a field where they’d grow marijuana to beat back all the aches and pains sure to accompany late-life infirmity. He’d call it The Peak, so named for a Cincinnati house he’d shared with fellow Beta Alpha Gamma brothers George and Rodney after they graduated from DePauw.

All my life I’d been a middle child adrift in a sea of ten siblings, the sixth son of transplanted black Southerners; he was an only child of white privilege whose prevailing self-image was that of an orphan left to rot with alien parents. The appeal of a home peopled with friends instead of blood relatives made sense and I fell willingly into his dream. Once we became lovers he expanded the dream of The Peak to include me, in a satirically racist tone: “…of course you’d have to come. Since you’re younger than us, chances are you’d still be in good shape, and…well, every estate needs a family retainer.”

I wanted to remind him of then, perhaps to distract us from the numbing chill that the Manhattan sun—glorious, fiery, blinding—couldn’t mollify. Instead I kept those visions of our past to myself, letting them mediate the current view of the man beside me, his large rheumy eyes crowding the other features on his macerated face. Only 38, he resembled some frightening male dowager, one of those cane-waving characters out of a screwball comedy. Wheelchair-bound now: AIDS had rendered him ancient, more Citizen Kane, a thousand rosebuds dangling on his pale thin lips.

At 36, I was too young to be a retainer, though a year’s accumulation of sleepless nights and waking preoccupations made me feel three times that. At least the park’s open burst of sky allowed me to imagine my friend and I were the last two people on earth. We’d planned our escape the night before—I’d actually heard a rare spark in his voice when I offered to take him out for a stroll in his wheelchair, then we’d spin around the park where we’d have privacy in public.

Except for his last trip home from the hospital he hadn’t been out in weeks. I’d hoped my gift—sunlight and fresh air—would be a distraction from the pills and his loft’s new claustrophobia, thanks to his parent’s arrival at the beginning of December. Since they arrived, we’d had no alone time. An outing would give us privacy in public.

He was my family that day, a kinship nearly sixteen years old. That spring I’d heard his voice calling out my name as if he’d been chasing me for days. He was a University of Cincinnati grad student who needed another actor for his directing thesis and I was an undergrad star of the theater department, an affirmative action baby with a talent for Shakespeare who’d already begun to work professionally. Dan made his case—he wanted me to play a Cockney thug in Pinter’s two-hander, The Dumbwaiter—as we stood in front of the department’s bulletin board. Tall, mustached, a boy-man with shoulder-length chestnut hair dressed in denim cutoffs; below them unfurled long tan legs atop bare feet. The sight of the last made my brain fuzzy, to the extent that I barely heard a word he said.

At rehearsals he’d sit on the studio’s floor, a gangle of limbs. I tried not to stare at his high-arches, their dusky insteps ringed pale like question marks. Once, the other actor was late and Dan told me his life story. His folks were from Michigan, but he was born in Davenport, Iowa; his father worked for Ralston-Purina and they’d moved around a lot…words, distractions from the provocation of sun-kissed toes and my mounting crush.

The afternoon of our Washington Park outing, Dan’s feet were encased in thick socks and dirty running shoes. A pair of too-loose jeans and an old coat whose thick tweedy fabric was originally drab brown speckled with white buried the rest of him; I’d had it dyed navy blue a few years before Dan and I broke up. The frayed wool cuffs reminded me that it was probably older than the two of us combined. Such coats were popular when we moved to Manhattan, though we were never able to affect that staple of 80’s style, rolled up sleeves, because the one physical trait we shared—long arms—made us look like hicks from Dogpatch. When he wore it he resembled a very tall crow, an image fostered by the coat’s cloak-like cut, the speed of his walk and his large beaked nose. The big mystery was how the coat wound up in his possession—had I given it to him or did he appropriate it earlier, one more sartorial theft enacted by couples since the dawn of man?

His mother loathed the coat. By then I’d grown used to Joyce’s anger, veiled in a politesse cultured in Cincinnati’s ultra-white suburbia. Such snipes—at the coat and our artistic aspirations to name but a few—were manifestations of the scant power she retained, an impotency exacerbated by New York, its D-Day nostalgia beloved by her husband but scorned by her. Or feared—in Manhattan she was out of her element, one minute dowdy compared to Dan’s tony female friends, the next, disoriented by the cramped Red Apple on Mercer Street. She’d been brought low by Dan’s calamity, but also the city’s chaos. Her superiority to Manhattan—“…a lady turned to me and said she knew I wasn’t from here because I looked so clean”—failed to shield her from a place so unlike her suburban Ohio cul-de-sac. In Manhattan, there was no controlling anything; the idea of a town that defied order shattered her sanity. That this unmooring (not Dan’s condition) was the true source of her grief, she communicated relentlessly. I hated, and pitied her for that.

◊

The year before, Dan had gone to Amsterdam. He’d rung in 1992 with his best friend Billy, a geology professor who was overseas for a conference. At night they hit the bars, but Billy’s days were taken up with seminars, leaving Dan to haunt the baths and the various coffee bars where he could buy and smoke grass and hashish without being hassled. The pictures Billy took showed a tall pale man wearing a rolled blue pakol, and a short green leather jacket more suited for the spring or fall. No doubt such a garment—tight, cut just so in back to frame the wearer’s buttocks provocatively—made Dan a man magnet in old Amsterdam, much as it had in the States.

Back in New York, his seductive powers waned as his cracks began to show. Chemo treatments for the Karposi’s sarcoma on his arms and legs thinned out his hair. His sensuous gay drawl grew quieter on the dwindling occasions we attended the theater, and when he showed up for dinner at a friend’s, it wouldn’t be long before he’d have to lie down. Sprawled on our various sofas, he’d sit and smile at jokes as we got him water or another pillow.

By then I’d grown used to men breaking down at dinnertime. Too many evenings I’d watched as the sly shock of AIDS plagued intimates and strangers through their appetites. At one friend’s West Village apartment, a beautiful black man my age had a long violent coughing fit during dessert; by the time he was done his voice had disappeared. On another night, the evening’s host took a few bites of the delicious stir-fry he’d prepared before returning his fork to the table, tense lips on a pale face beating back nausea. High drama—and sly comedy, especially in the ways men sought to keep their status private: the discretion award went to a pal who surreptitiously downed his antivirals between bites at an Indian restaurant on East 6thStreet. I wonder if I was the only one who noticed.

Eating was but one of Dan’s issues. To combat gastrointestinal parasites, his flagyl treatments continued. His doctors took him off AZT and put him on DDI, a new antiviral. Maybe Dan was too overwhelmed by his other symptoms to note the early tingling sensation in his toes and feet; by the time he complained of numbness in his ankles, it was too late. The experts called it DSP, or distal sensory polyneuropathy: the nerve damage was a notable side effect of both flagyl and DDI. Those beautiful feet were suddenly useless, and as his long loping stride gave way to a tentative limp, like a colt hobbling on broken glass. Still, he refused to carry a cane

That July I’d thrown an afternoon party at our old place. An hour or so after everyone had arrived, the buzzer rang and over the intercom I heard a breathless, “It’s me.” I went out to wait in the hall and listened, as the sound of panting preceded his slow crawl up five flights. His arrivals were always fraught in those days, but that afternoon he appeared on the verge of hysteria, as if he’d escaped a mugging. Dressed in denim cutoffs, and a sleeveless shirt that revealed a bandage covering a patch of recently lazered KS, he collapsed on the steps as soon as he reached my floor.

Somehow he’d taken the wrong train from the Village, and had wound up in the Bronx. He’d managed to double back but getting lost had terrified him. Perspiration from the day’s humidity darkened the light blue of his shirt.

“You’re fine, now,” I murmured as I stroked his downy head. He wore his chemo-thinned hair in a buzz cut; the remaining tufts of chestnut shot through with white and gray accentuated a premature impression of old age.

“My feet really hurt so much. I can’t train it back.”

I took his hand. “Look, there are a bunch of folks here who’ll be going back downtown. We’ll get you home, okay?”

I ushered him into the apartment, my hand at his back for subtle support. He recovered quickly—during the party he sat on the couch, holding court as friends spoiled him with attention, nudging his surrender to the day’s high spirits.

It was the last time I’d see any semblance of the old Dan. In September, I came down after work to drop off cans of Nutrament. The high-calorie protein drink was the only food he consistently took by mouth, but he hadn’t the energy to carry groceries. When I walked through the door I was blindsided by a nauseating stench; as I unpacked his groceries I heard rustling overhead in the loft bed built above his kitchen. He’d been in bed the whole day. When I mentioned the smell, he confessed that the drugs were re-arranging his insides so unpredictably that he couldn’t always make it to the bathroom.

The culprits were all lined up on the kitchen counter, brown plastic vials of miracles meant to forestall the virus’ complications: Epogen for his AZT-related anemia; Ganciclovir to head off CMV, an eye infection that could blind him; fluconazole to keep fungal infections in check, and pentamidine to guard against the deadliest threat, PCP—pneumonia. Their side effects only exacerbated the wasting by killing his appetite: even the sight of food made him nauseous. And on those occasions when he actually desired a meal, the medications made it impossible for normal digestion. It was no longer a question of whether diarrhea would occur—only when. He didn’t have any choice but to endure; his “dolls” as he quipped at rare stabs at humor, were keeping him alive.

Pot gave him his only comfort. He always had a large bag of it around in those days, a supply that rarely ran low since few of our friends smoked anymore. Sometimes I’d have a toke, but he could keep the bowl lit all night, when he wasn’t chain-smoking menthol Benson and Hedges. The cigarettes appeared around the time of his diagnosis; though I’d lectured him on the dangers of further weakening his immune system, he refused to stop.

At the beginning of November they installed the Hickman—a port with external catheters that dangled from the center of his chest like stunted tentacles. In addition to the nurse who came daily to check the IV lines, I scheduled friends to run errands and look in on him—but after he was hospitalized for the second time that month his parents could no longer be left out of the picture. Helen elected to make the call. She and Dan had attended DePauw together; after we moved to New York, she became one of our closest friends. Dan didn’t want them to come, but by then someone had to be with him all the time.

Days before his folks arrived we cleared out his marijuana and cigarettes, his bongs, his porn and other incriminations: he’d warned us that Joyce was a notorious snoop. I couldn’t imagine the withdrawal from the nicotine and the pot, or that he’d have nothing to take the edge off while the pharmaceuticals turned him inside out. Some friends we were: to me, taking away his only means of escape was the ultimate cruelty.

1992 was one of the busiest years of my performing life. Soon after Dan’s Amsterdam trip I was hired for my first Broadway workshop: ‘39 was a show built on the songs of Harold Arlen. Rocco Landesman was producing; The Secret Garden’s Susan H. Schulman helmed a cast that included the great Philip Bosco, among others. The achievement belonged dually to Dan and me—this was the reward for the indignity of our salad days and a life consumed by the treadmill of auditions. Every night I’d call him to share news of the day’s rehearsals and my state of mind, as I reeled between elation and insecurity.

Even in sickness, Dan remained my Svengali. The idea of my doing a one-person show sprang from his assertion that I’d feel better about the ups and downs of show business if I had some control over some aspect of my performing life. That May we mounted a show of songs and monologues at Soho Rep where our playwriting workshop was in residence. Luck intersected with ambition: my musical director got wind of a cancelled booking uptown—on his recommendation I found myself booked at Danny’s Skylight Room on 46thSt, a spot that would become my cabaret home

I was grateful our cabaret work had taken off because it meant evenings at his place. We talked on the phone all the time, but those conversations were no substitute for a visit where I could see how he was. I needed reassurance that he was alright; rehearsals were a way for me to check in without being intrusive, or horrors, a mother hen. We rarely spoke of his illness, probably because Dan had little use for self-pity, or the confessional. Keeping it hid was his way, but I hoped our nights spent working on patter and songs were at least a distraction from his own preoccupations.

In the two years since Dan and I broke up, every relationship I attempted failed to take hold. All came stamped with a six-month expiration date, like the one with Tim, a lawyer I’d been seeing until shortly after Dan came back from Amsterdam. It was only my second dating experience as a gay man. I was needy, a trait that ill-suited me for the rituals of courtship. Dating was a consistent disaster: it didn’t work out with the East Village housepainter, the student in Soho or the French shoe designer either. I had no patience for, nor much knowledge of, the coy games dating required. Those guys lingered at the starting line; I was already at the altar.

So I had sex instead. Before Dan moved to the Village in the winter of 1990, I’d already discovered a Times Square full of peepshows, and while I waited for the real thing I let myself be distracted by a trail of anonymous men. At the end of a six-month dalliance I’d return to those dark backrooms concealed by absurd beaded curtains, where you’d have to go either upstairs or down: rarely were these sections of the porn shops—with names like the Meat Hook or The Male Box—on the main floor. On a lunch hour or after work, I’d wander over to 42nd Street for the hope of a caress through a clear Plexiglas partition raised waist high to create a glory hole large enough for a penis, or if I was lucky, an arm or a face. There I could kiss a stranger, or have him hold my hand while his mouth engulfed my cock. No games here: eye contact and a nod of consent made such fleeting intimacies happen. Sometimes I meet guys who wanted to see me again, but neither of us ever had an expectation we’d progress beyond fuck buddies.

Maybe that was all I’d been capable of. There I was in my mid-30s, sowing wild oats that’d been bottled up since I first laid eyes on Dan. That I hadn’t descended to total depravity became evident when I found myself fantasizing a life of domesticity with myriad tricks. If the guy wore a suit, or showed some depth of character, I immediately imagined what it’d be like to spend evenings with him curled in front of the TV, or mornings when I’d make him breakfast.

It was ridiculous and revelatory: in the guise of lust I’d sought to assuage loneliness. All the quickie sex juxtaposed with all my pickups, who interspersed with men I “dated” in desperate attempts to fill the gaping void left by Dan. Such encounters only accelerated as Dan’s condition worsened—grief fucking was what one trick called it, and while he rightly perceived I was mourning the end of my relationship, that stranger couldn’t have known what seemed clear to a doctor friend: after I told him Dan had KS lesions on his biceps, he said it was a sure sign the AIDS had progressed beyond repair.

Those episodes of sex in back room and strange apartments fed the year’s other addiction: habitual HIV testing. My first had been in early 1991, weeks after Dan told me his status. His assurance that he’d been faithful seemed unrealistic given the speed with which he’d gone from positive status to full-blown AIDS. But he was what the experts called a rapid progressor, one of many who defied the 10-year incubation theory; for reasons unknown their immune systems cowered in the virus’ presence. Rapid progressors weren’t the norm, but their numbers were growing as the virus mutated faster than science’s ability to track or contain it.

I tested negative. The results were the same six months after that, but I kept going back. Sometimes it was the hysterical fear that I’d slipped during an encounter, but the underlining reason was the belief that Dan and I were destined to walk the same path. I met a lot of guys who felt certain that inevitably they’d go the way of their friends and ex-lovers. Luck spared us, we reasoned; dumb luck seized our cronies. Guilt on top of grief—it gnawed and churned, keeping me up most nights—and the only remedy was the sound of those health department counselors cooing, “you’re negative.” Their reassurances lasted about as long as my relationships. Within months my dread would re-surface and I’d call for another test.

◊

Like a mother—I imagined I knew what it was to be Joyce, wondering if your actions were the wrong ones, if your mistakes made him worse, not better. Remembering his blue wool coat was unlined added one more notch to my tally of lapses though last fall’s was the worst; after an early evening appointment at Columbia-Presbyterian, he asked if he could crash overnight at my apartment—our old place. Over dinner he regaled me with his medical mishaps. At the hospital drinking the flagyl made him gag, an embarrassment because the doctor was cute. Getting a cab was easy, but as he slowly climbed the stairs to the apartment a neighborhood stared at him, perhaps mistaking his fractured walk for drunkiness.

Pushing around his pasta and zucchini, he’d asked a question that caught me off guard: “So, are you dating anyone?” The leer in his voice was unmistakable: it never occurred to me to ask about his love life, and I tried to remember how often I’d seen this teasing Dan, someone who could talk openly about sex or drop bits of provocation for shock value. Despite the virus coursing through his body, he was still a sexual being, something I hadn’t allowed as a possibility. I realized his curiosity was an attempt to re-cast our relationship as something more casual, more comrades than ex-lovers. I couldn’t make the leap: call it shyness or shame, but my myriad pickups or the wasted hours I’d spent trolling for sex was the last thing I wanted to share. I didn’t want to discuss the times I’d been stood up, the guys who failed to return my calls after a single date or lonesome Sunday afternoons spent roaming the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Such confessions would surely invite his pity; I was too proud to reveal this particular failure. So I lied, ending the conversation with a quip: “Yeah, there’s someone but it’s too early to bring him home to Mother.”

Hours after we’d gone to bed, he called out from the other room. I walked in to find his teeth chattering, eyes wild. I put on the kettle and grabbed another blanket from his old closet. For a while we sat there silently drinking peppermint tea. An eternity passed before he felt warm enough to fall asleep. As the clanging steam pipes signaled morning, I kissed his balding buzz cut goodnight.

When I left for the day, he was still asleep. Later he called me at work to say he’d had an accident; that evening I came home to an apartment reeking of the odor I recognized from his loft, a smell no amount of ammonia or bleach seemed to expunge. Scrubbing the hallway floor, delayed clarity trumped the nauseous odor of diarrhea. My body heat would have warmed him quicker than the tea. I dredged soiled sheets in the bathtub, and kicked myself for freezing in the headlights of his illness. I should have gotten into bed with him last night. Stupid fear had shut down my brain and rendered me useless.

I learned the mechanics of his mediport, a contraption best described as a computerized IV pole. From it hung plastic kidney shaped bags filled with milky emulsions—the doctors called them infusions, essential nutrients that kept him alive once he lost his willingness to eat. Someone else besides him had to know the mechanics of hooking the bag to the machine, but also how to maintain his Hickman. His Asian nurse cautioned me on the dangers of infection, and how it was essential to flush the valves with clot-preventing heparin.

So much to remember: what if I forgot to clean the sharp before inserting it into the lumen? What if the heparin didn’t work? What if I couldn’t turn off the stupid admonishing alarm that signaled the machine’s malfunction? During hospital visits it went off constantly, an annoyed high-pitched electronic pulse that only the nurses could silence. That disembodied squeal invaded my dreams, reverberating like a conscience.

◊

After the park we navigated the cracked, empty sidewalks on Washington Place. Turning left onto Broadway, a shock of chilly wind made my eyes tear, and Dan muttered an audible “Jesus fuck.” Soup ‘n’ Burger neon sign beckoned and I remembered thinking how I’d passed it a thousand times but had never gone inside. The place looked full, but his wheelchair got a waiter’s quick sympathy; having rescued us from the cold, I found myself flushed with an odd, fresh happiness. I ordered tea for us both, followed by vegetable soup and a cheeseburger we opted to share. I watched him peck at the soup, but he took no pleasure in the meal, which deflated my hunger.

When we first met, he’d make a big stink when a hunger headache surfaced, and whatever engaged us at the moment lurched to a halt so he could shove something in his mouth. He’d eat with his eyes closed, his face radiating comic mock rapture. So much of his pleasure had been tied to food; our early New York years were marked by stacks of cheap toasted white bread slathered with butter and his favorite dinner of burger and noodles, wolfed down in our kitchen on a folding card table covered with a yellow vinyl cloth. Cheap and filling was his motto: $1.99 for a six-pack of beer, or macaroni and cheese, 4 boxes for a dollar at the local supermarket.

Over such meals we’d mapped out our lives. There was that late spring afternoon when, over a Coke and a cheeseburger, he asked if we could be together. I’d not yet turned 21. He presented the thing I’d determined was impossible—love—so simply as we sat in the Student Union Food Court surrounded by the din of peers swamped by upcoming finals, baby men and women contemplating summer jobs or hung over after a night spent drinking pitchers at Jefferson Bar. That was us, zipping from one Cincinnati convenience store to the next in his Ford Pinto, his beloved Pink Floyd blared from the car’s cassette deck—riding the gravy trainwailed the car’s speakers, a naïve mantra summoning destiny as we ate Doritos on our way to a movie, or his studio apartment to make love.

Our lives were lived to the tune of an FM Radio, when we weren’t gobbling up the latest original cast albums from a Broadway we hoped one day to take by storm. We were both singers enthralled by the sound of a beat or the passionate heartbreak of a pop song. His tastes were myriad and revelatory to someone who’d grown up on R&B and a steady diet of Motown, but in no time he’d turned me on to the virtues of art rock and the Doors.

He was obsessed with the Floyd. They took all of his guilty pleasures—heavily orchestrated rock, beautiful songs and vocals that hummed with naked emotion—and served them up in a synthesized wash of aural hallucinations, Valhallian soundscapes careening from dead calm to rampant chaotic opera. Pot was the perfect drug for the toy sounds of whistles and bells weaving through their outrageous suites—but a melancholy disposition with a dusting of nihilism also helped the appreciation along: that’s where Dan came in, simultaneously mourning for his life and at a remove from it. He’d found his soundtrack.

At Soup ‘n’ Burger, the music droned imperceptibly. People murmured; stainless pinged against porcelain plates and coffee cup walls. Through the diner’s dim glow words eluded the volumes hanging in the air. The looks we give each other are hoisted by memory. The waiter breaks the spell—anything else? We ordered more tea as he broached the subject of his mother’s enduring harangue. She saw his illness as a personal failing. Frequently she moaned about the unforgivable way he let her down. Such moments revealed his transparent hurt, and as I listened I thought how eternal, the way gay men are tyrannized in their yearning for an acceptance that rarely comes. I get that he’s their big investment, but how exhausting to have all their hopes and dreams pinned on one child.

Did they love him? I tried to look past his reports of motherly abuse, tried to imagine that she and I felt the same pain. Maybe her complaining was about denial; how better to forestall the realization that soon she’d lose her only son. But with so little time left, I failed to understand why she couldn’t leap out of contentiousness into love. Dan’s tales only confirmed how hard she tried to make his illness about her—she was the one who’d been lied to, she was the one who’d been betrayed.

Such revelations never lost their ability to stun. Each time I listened, incredulous that an otherwise intelligent woman couldn’t grasp how quickly time was running out. I couldn’t help but think of that November evening at his loft, weeks before Joyce and Bill arrived. By then the place resembled a rather large hospital room: brown prescription vials littered the kitchen counter, while nearby stood a stack of brown boxes. Some contained clear plastic bags of glucose for his IV; the others were filled with the thick infusions. A wheelchair lay propped against a wall.

He didn’t want to take his medicine anymore. It was more than the pain that came with his attempts to swallow—a week earlier he’d moaned, “I feel like one big pill. I can’t believe this is my life now. Flush them, Ennis.” His request terrified me, and for a few minutes I tried everything I could think of to make him rethink his choice but the look in his eyes—weary, panicked—convinced me he’d had enough. That night I watched confetti dots of white and color swirl down the drain along with my already fragile hope. Helping him die meant I was giving up too—or letting him go with grace.

I’d been well rehearsed in saying goodbye. It began the week after he got his new job when he’d said, “I’m sorry to be leaving you behind.” I thought he meant at the office where we were both employed at the time, but by then he knew he’d fallen out of love. The day he left it rained. When the movers arrived, we hugged, full of promises we’d talk soon, then I practically ran out the door. When I returned, our empty home was much as it had looked when we moved there six years prior. He’d left an envelope with my name poised under a lamp, a letter of thanks for our years together, expressing a desire to stay the best of friends, full of memories and long-forgotten details from our earlier life. I re-arranged what remained and cleaned until midnight.

I snuck a look across the lacquered table. He caught me with a smile poised as a question, so redolent of Dan from days long gone. I smiled back, tapping my knees against his under the table. Outside, the Broadway afternoon faded into early night. We’d been gone for a while, and though neither of us wanted to leave I could tell he was tired—he had such a short shelf life then—so I asked for the check, unfolded his cumbersome wheelchair and sat back down. Who are you now, went a lyric from Funny Girl, a show he loved. His gray-blue orbs, from which I’d learned that a man’s eyes determined whether or not I found him attractive, were dull black holes of fatigue. The large broken nose and those funny ears showed faint hints of the man I fell in love with at first sight, but his head looked naked without hair, parchment skin revealing contours of bones traced with veins. I smiled at him again, a tight grimace this side of tears as I realized how much of that 22 year-old boy—the one who ambled barefoot into my life too many springs ago—had vanished. Who are you now?

◊◊◊

Wheeling him down Waverly toward Greene, I’d instinctively glanced up at the row of fire escapes on his building’s façade. Last summer came crashing back, sunny Saturdays when my long runs from our old place in Harlem Heights would end here; turning off Fifth Avenue, I’d look up to see him propped up against a pillow, his long legs—gams—in triangulated silhouette. Head covered in a bandana. Reading, always reading. I’d let myself in with his key, grab a glass of water and join him, our small talk drifting in and out of conversations wafting up from the street below.

Our first apartment, at 860 Riverside Drive, had a fire escape nestled in the canyon between our building and a smaller one across the way. It led to the roof and on the hottest days he and I’d climb up and down, carrying drinks, newspapers and games as we relished the breeze that buckled and snapped the canyon’s matrix of clotheslines weighed with diapers, shirts and kitchen towels. Weekend afternoons sauntered along as I watched him bake his long limbs tawny.

The Peak East. Within a week of moving in, a cat burglar came down the escape from the roof, slid his knife between the window frames and made off with our television, a few pairs of jeans and my high school class ring. Fortunately he didn’t get our stash of weed, and after the cops left, we got stupidly high. A friend gave us an old TV. We used a wire hanger for an antenna.

Our sink fell off the bathroom wall, flooding our floor and the apartment below. Another burglary followed: they kicked in the door while he was away and I was at work and took the stereo. I cut Dan’s hair, and taught him how to iron and sew on buttons; he taught me how to balance a checkbook. Together we learned to refinish cast-off furniture found in the street. Both of us became better cooks, thanks to the Sunday Times and the legions of smothering women we met in our building and through temp jobs. We helped each other with auditions and when acting work came, with lines. The winter I had two impacted molars extracted, Dan brought me home from Mount Sinai, filled my prescriptions, brought me chocolate milkshakes and held my aching head like a mother.

For the first few years his parents flew him back to Ohio for Christmas, leaving me to an unwelcome Manhattan solitude. But the year he resolved to forego Cincinnati Christmases forever, we celebrated: after dinner at Luchows on 14th Street, fueled by champagne and joints, we blew up the entire contents of a few dime store bags of balloons, filling the living room space of our tiny 2½ rooms with orbs of red, blue, orange, yellow, pink and green. We dropped them one by one out of the window into the canyon; the colored bubbles filled with warmth breath lolled in the cold air before drifting into the pitch-black alley below.

It’s similarly dark when we arrive at his loft. Joyce waited at the door, her pinched face poised to administer more of her killing love, eyes permanently narrowed in reproach. Long gone is the woman who, in 1978, packed us bologna and butter sandwiches on white bread for the long drive from Cincinnati to New York, the one who cried as she kissed us goodbye, entrusting her only child to a future she didn’t recognize or understand.

After I settled Dan on the sofa that now served as his bed, Joyce and Bill retreated to his kitchen, preoccupied by their new obsession: store-bought frozen dinners. The kitchen was less than 15 feet away so it surprised me when he curled himself into my lap and fell asleep, but it also made sense: he’d grown too tired to care what his folks, or anyone else thought. A car commercial flickered on the TV as I stroked his soft bony head, its frail wisps of hair still strong with his damp aroma. Dead to the world, I thought, pondering the truth such an innocent axiom held. He was Sleeping Beauty, except there’d be no magic kiss to wake him up, sweep away the briars and turn back the clock to the way it was. He was.

On my way home I walked past the park. Right before McDougal Alley, amber light welled from the tall windows of a red brick brownstone. Dreaming of lives beyond those walls made me long for balloons and cheap six-packs, for 2½ rooms and the days before words like positive and T-cells. I ached for one of those evenings after Dan had finished working on a script, when a mellow tune would swell on the stereo and a tall man with a broken nose and tossed brown hair would pull me into his arms for a slow dance before dinnertime.

It dawned that I should call someone when I got home that night—his friends, spread out far beyond the Hudson surely wondered how he was getting on. Maybe I could’ve chattered away the lump in my throat. But as I waited for the A train, I discarded the notion—that night the only voice I craved belonged to a man I knew was already fast asleep on a sofa, his size 9 feet swaddled in thick blue socks.

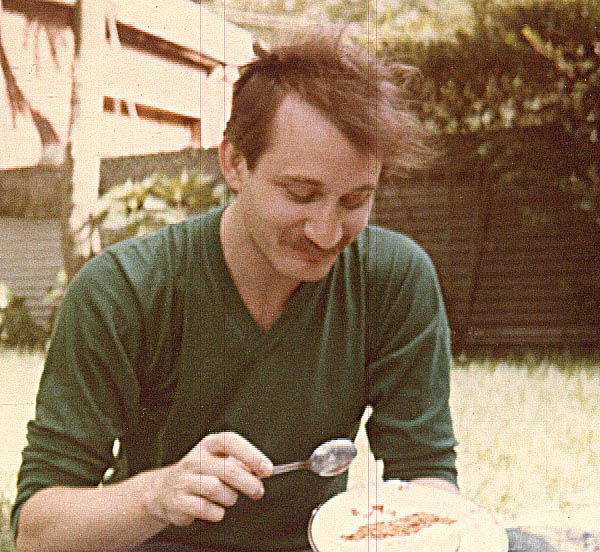

Above, Dan in the early 80’s. Photo: Janice Grant