Perhaps he might have noticed the headache first. With the onset of HIV it would have been atypical, a persistent buzzing immune to aspirin, ibuprofen or acetaminophen. Rolling from the base of his skull to the crest of his furrowed brow, it would have been a sensation freighted with the heaviness of an eternal cloudy day. Dan might have easily reasoned such occurrences away; hunger was the cause, he’d opine, or the raging demands of his newly single life, one requiring what the queens referred to as a gay nap, from which he’d spring into the shower, then out onto the streets of Chelsea and the Village, to clubs named Cock, Spike or Dudgeon, to various discos, bars and backrooms. This part of his social life wouldn’t take flight until past 10pm; beer, joints and poppers would feed the headache accompanying his perpetual prowl. Come morning, the wave of fatigue coloring every action would feel well earned. All could be blamed on the night before.

Perhaps he might have noticed the headache first. With the onset of HIV it would have been atypical, a persistent buzzing immune to aspirin, ibuprofen or acetaminophen. Rolling from the base of his skull to the crest of his furrowed brow, it would have been a sensation freighted with the heaviness of an eternal cloudy day. Dan might have easily reasoned such occurrences away; hunger was the cause, he’d opine, or the raging demands of his newly single life, one requiring what the queens referred to as a gay nap, from which he’d spring into the shower, then out onto the streets of Chelsea and the Village, to clubs named Cock, Spike or Dudgeon, to various discos, bars and backrooms. This part of his social life wouldn’t take flight until past 10pm; beer, joints and poppers would feed the headache accompanying his perpetual prowl. Come morning, the wave of fatigue coloring every action would feel well earned. All could be blamed on the night before.

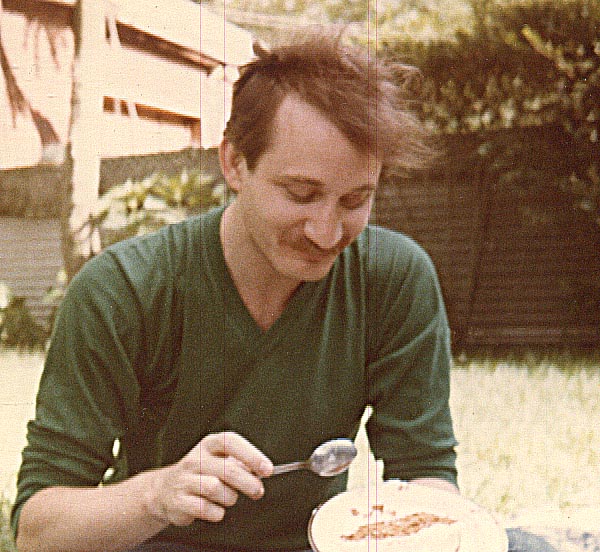

The weight loss would give him pause, but that too he could dismiss though this denial would take effort. Ask any of his friends—hell, ask me: for as long as I’d known him, Dan had always possessed a powerful appetite. Never one to miss a meal went the joke, one confirmed countless times by his tedious complaints of a…headache, he was so hungry. Now that he was paying a mortgage instead of splitting cheap rent, dinners out were few, and more and more he’d resist the urge to reach for the takeout menu. Instead he regressed to the eating habits of our early New York youth, years notable for meals of macaroni and cheese bought at the Red Apple at the then-bargain price of four boxes for a dollar. Months after he moved out of our place, I got a phone message requesting a recipe for yogurt muffins to augment bag lunches filled with fruit and cottage cheese, a cheaper option that an expensive deli sandwich. Be it economics or illness: whatever the reason, the dropped pounds would be seen as a gift especially now that he was single and back on the market. As a new denizen of the lower East Side he had to look good in jeans, which to some minds meant having a form that disappeared in them.

Even if his taste had changed, he would have ignored the other adventures unfolding on his tongue or gums. Complaints about eruptions were legendary—his rants about his chancre sores or the occasional pimple had long peppered our conversations. Warts were an ever-flowing pox that dotted his fingers, elbows and once, painfully, his anus. But maybe there had been no oral symptoms; surely his dentist would caught them that spring morning in 1990 when he got a set of porcelain veneers, a remedy for the small teeth he loathed, an expensive splurge or a gift from his folks—I never learned which.

I also couldn’t have said if he’d showed signs of a cold or the flu. Now that he lived alone, there was no one to record the flux—nor to tuck back the tag on his shirt collar, or retrieve that bloody speck of tissue from his chin before he headed out the door. When the breakup came I embraced distance rather than proximity, opting to see him as little as possible though certain events were unavoidable, like our Saturday morning playwriting workshop. For all my dodging, not many days passed without a call, either to say hello or make a mundane request, something along the lines of “I can never remember so-and-so’s birthday—do you have that date handy?” I’d doubt the voice on the line would yield a clue if something were amiss; well or ill, his radiant baritone twang would trump nuance, revealing only the fact of his Midwestern origins with a music so pervasive even I would find it difficult to hear anything else.

This sort of blindness plagued me the December afternoon I arrived at his loft to find him prone next to his sofa. All of it –the closed eyes, hands clutching some discomfort buried deep in his back and midsection—remembered our final summer in Cincinnati. We were acting in a summer stock production of Gypsy when midway through the run he began to complain of a fatigue that grew steadily, to the point where he’d come offstage and have to lie down. Then it was hepatitis; the assumption was that he’d contracted it again.

Our friends Francis and Julie had arrived earlier to take him to Cabrini Hospital; my task required I stay behind. As we helped him to his feet, he fixed me with an urgent stare. “We called my folks before you came and they’ll be here tomorrow. You have to clean this place out.”

I rubbed his warm neck, flashing a conspiratorial smile. “I know—take the weed and porno back to my place. Don’t worry, they won’t find anything.”

In the end it turned out not to be what we thought. Later Dan would reveal that the doctor confirmed his own hunch. But when did he know? Maybe intuition came while deep in a dream of anesthesia as they removed what remained of his gall bladder, or after, as he rose from its fog. Revelation might’ve come months sooner, when the headache, hunger and his diminishing frame pulled him up short, punched him down after one too many nights out.

He broke the news to me over New Year’s Eve Dinner. What followed were his own reassurances that I had nothing to fear, but all I could think of was the month before: the urgent stare before he left for the hospital, grey-blue eyes brimming with a truth larger than the fear of his folks, or my amateur speculations based on a far-away past.